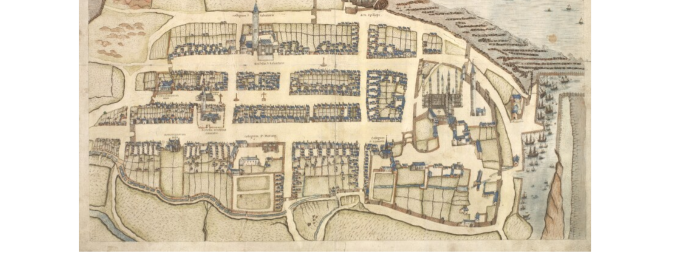

"We build our computer (systems) the way we build our cities: over time, without a plan, on top of ruins." - Ellen Ullman

John Geddy’s map of St Andrews, c.1580. National Library of Scotland (MS.20996) http://maps.nls.uk/view/00001427

St Andrews in 2017. © OpenStreetMap contributors http://www.openstreetmap.org/copyright

Here at the University of St Andrews Library, we’re fortunate to bemembers of the JISC RDSS pilot.This involves, among other things, selecting a digital preservation system for our research data — once in production, the use of this system could expand to other use cases including corporate records, born-digital manuscripts, digitised special collections material, and more. The project is likely to increase the number of institutions in the UK with in-production preservation systems —part of what has been called on this blog the ‘new round of repository procurement’ — due in no small part to brave initiative-taking by JISC,decreasingimplementation costsand effective digital preservation advocacy.

This is a welcome trickling-down of digital preservationcapability– as recently as 2013, RLUK reported in their ‘Survey of Special Collections and Archives in the United Kingdom and Ireland’ that a ‘dramatic finding … is that current collecting of born-digital materials and the expertise to manage them are concentrated in a very small number of institutions that already hold a significant amount of digital materials—while most others have very little or none (median holdings are zero)’. This could also represent a small step towards the decentralised digital archivenetworkmany of us would like to see.

However, being a pilot on this project is not without its challenges —one of mine is: how to choosea necessarily generic preservation system that can fit with our different workflows, use cases and data types — while knowing thatrequirements willchange and emerge during the lifetime of the system? The short answer is that this involves a lot of uncertainty —though system vendors might disagree!

The systems on offer are broadly similar in their philosophy, tools and standards — all leave me worried about (i) automation and (ii)future interoperability.

(i) The volumes of data we must preserve demand a largely automated solution — do we have enough control over the creation of our data to ensure this won't be a case of 'garbage in, garbage out'? When would we be able to tell if this were happening, and would we be able to fix it?Better data and records management may be the only viable answer until AI begins to solve these problems — but this is easier said than done and requires a whole new level of resource. I don't think it's something we can expect our preservation systems to fix for us, so for now we run the risk of creating digital archives of little value.

(ii) Discussions about largely automated black box preservation solutions are both pessimistic about the future (hoping to be ‘future proof’) while also being optimistic (anything that doesn't work now can be solved by our successors). Whatever system we put in place is likely to be there for some time — and the more we use it, the more painful it will be to turn it in to something else. Looking around the library, I can see systems that may have worked well in their time — but it didn’t take long before they became a problem, a legacy to be coped with, an expensive system to maintain or migrate from. Desiring future interoperability puts us in the difficult situation of needing to define more precisely what we mean by an AIP, how we create it and move it — while also desiring flexibility to cope with future preservation use cases. I'm keeping an eye on the E-Ark project, use of APIs for data export, and working with vendors to better understand the implications of their AIP structures – but this is a developing area and not a solved issue.

If we can't have a 'future proof' system, I'd at least like to lay foundations that don't burden my successors with expensive, difficult, or unsolveable problems - something librarians and archivists working in medieval universities will be familiar with.

St Andrews Cathedral – Once greatly admired, expensively developed infrastructure allowed to fall into ruin as requirements changed. © User:e6La3BaNo / Wikimedia Commons / CC-BY-SA-3.0