I have recently travelled from Melbourne, Australia to work on a three-month research project with the Digital Preservation Team at the British Library. This project will explore the role of virus checking in long-term collection management and digital preservation.

Computer viruses are a form of malware—an umbrella term which refers to various types of ‘malicious software,’ including viruses, spyware, ransomware, worms and Trojan horses (Symantec Corporation n.d.). Viruses are programs that can be disruptive and destructive to computer environments by displaying unwanted messages, deleting files or removing the BIOS (basic input/output system) so that the computer can no longer start up.

Over the decades, the prevalence of malware has grown exponentially and an entire computer security industry has grown in response. As such, it has now become commonplace for users to experience malware threats, especially through online activities. Also, it is not unusual for stories about malware to hit the news. For example, the WannaCry ransomware attack of May 2017, which targeted computers running the Windows operating system made headlines when the infection managed to shut down machines in over 80 NHS organisations across England (Hern 2017).

Despite the fact that all digital collections and technical environments are susceptible to computer viruses and malware, this is – surprisingly – an area that has not been thoroughly explored by the digital preservation profession to date. Aside from interesting research conducted by Jonathan Farbowitz (2016), which advocates the notion of institutions preserving malware for history and study; exploring malware through a digital preservation lens is a new (and exciting!) research endeavour for the digital preservation field.

The research project I am undertaking with the British Library aims to provide insight into some of the many questions we could ask ourselves about the function of virus checking in long term digital preservation. We will begin by exploring the types of viruses that have been detected in some of the Library’s collections. We are interested in the risks that these viruses pose long-term, as well as trying to better understand exactly when virus checking should actually take place. This is a very important question when operating at scale and considering a) the overhead this introduces into the process and b) the uncertainty about the benefits it brings. I will explore these questions at the Library by investigating literature on malware and reviewing some legacy and contemporary viruses in selected collections.

For example, working with the Library’s technical and preservation specialists, I will examine the types of viruses present in some of the disk images generated as part of the Flashback project (Day et al. 2016).

Sample of disks imaged as part of the British Library’s Flashback project.

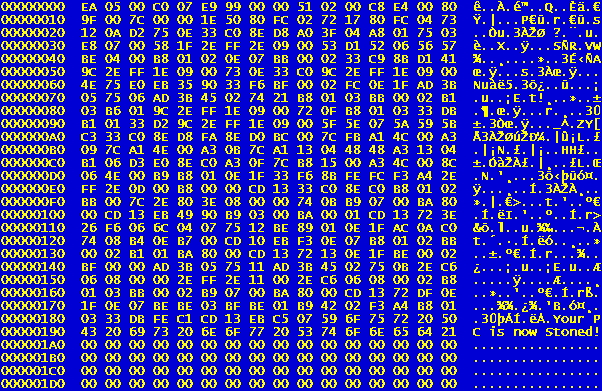

These are typically ‘old school’ types of malware which were transmitted via floppy disks and CD-ROMs decades ago. Examples of these types of legacy malware may include boot sector viruses such as the ‘Stoned’ virus, which was created in 1987.

Hex (base 16) dump of the Stoned virus—one of the very first known computer viruses. A computer infected with the original version of this virus, had a one in eight chance that the screen would display the phrase: "Your PC is now Stoned!". Image source: Wikimedia Commons.

Alongside the legacy Flashback project media, I will also work with the Library’s Web Archiving team to explore a sample of their virus-positive collections. By analysing both legacy and modern digital collections, I hope to gain insights into the risks that both older viruses and more modern malware pose to the Library and its users. The project should also provide some valuable information so that the Library can make decisions about what to do with virus-positive collection material in the long-term.

As part of the project, I also hope to test some different types of anti-virus software with legacy collection content to determine if and how the results differ between them.

Having only three months, I am mindful that I may not be able to find all the answers and information. However, making a start in this area of research and raising awareness will hopefully be a rewarding and useful endeavour.

Maintaining the integrity of our collections over time is paramount. But how we do this, certainly deserves examination so we can adequately assess and understand the risks regarding malware in long-term digital collections and the effectiveness of our virus checking activities in our digital preservation work flows.

References:

Day, M., Pennock, M., May, P., Davies, K., Whibley, S., Kimura, A. & Halvarsson, E. 2016, 'The preservation of disk-based content at the British Library: Lessons from the Flashback project', Alexandria: The Journal of National and International Library and Information Issues, vol. 26, no. 3, pp. 216–34, viewed 11 September 2018, <http://journals.sagepub.com.ezproxy.lib.uts.edu.au/doi/pdf/10.1177/0955749016669775>.

Farbowitz, J. 2016, 'More than digital dirt: Preserving malware in archives, museums, and libraries', MA thesis, New York University, viewed 11 September 2018, <https://www.nyu.edu/tisch/preservation/program/student_work/2016spring/16s_thesis_farbowitz_final.pdf>.

Hern, A. 2017, 'WannaCry, Petya, NotPetya: How ransomware hit the big time in 2017', The Guardian, viewed 3 October 2018, <https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2017/dec/30/wannacry-petya-notpetya-ransomware>.

Symantec Corporation n.d., 'What is malware and how can we prevent it?', Malware, viewed 21 September 2018, <https://us.norton.com/internetsecurity-malware.html>.