The DPC recently held a series of events on the topic of digital forensics (an initial event on the 26th February and a follow up ‘Watch Party’ event suitable for community members in Australasia and Asia Pacific). As suggested by the title, the focus was to ‘investigate good practice’ through the sharing of knowledge, experiences and case studies.

This event was born as a result of the interesting discussions in our very first DPC Reading Club which looked at an article on the topic of digital forensics by Thorsten Ries, alongside a realization that our existing Technology Watch Report on the topic was in need of revision, and that facilitating a community discussion around the subject might be a good way to kick this off.

Above: Some of the speakers and attendees at a recent online event “Digital forensics and digital preservation: Investigating good practice”

As an aside, the DPC’s last ‘briefing day’ style event on the topic of digital forensics was an in-person event held in 2011. I remember being there, but had to search for my notes to find out more about the content (my memory isn’t that good). I found the notes from that event (plus a ‘to do’ list and write up that I’d shared with colleagues) on a portable hard drive – I considered that a big digital preservation win!

It was interesting reviewing those notes at the same time as I reflected on this most recent event. It is certainly the case that community knowledge and awareness of digital forensics has moved on since 2011 and that it has come a long way from being just “a promising source of tools and approaches for facilitating digital preservation and curation” as described by Jeremy Leighton John in his Technology Watch Report.

Whereas the 2011 event focused more on understanding the potential of digital forensics and on new tools and projects, our speakers in 2024 described their active use of some of the established digital forensics tools and techniques that are now fully embedded in their workflows as well as flagging up thriving communities that have formed around this topic. For example, Cal Lee from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill mentioned the 10th anniversary of the BitCurator Forum, and one of our other talks was from DANNNG - the Digital Archival traNsfer, iNgest, and packagiNg Group. This group has been busy creating helpful resources, such as their Technical Glossary and Disk Imaging Decision Factors guidance over the last few years.

Given the maturity that has naturally come with the passing of time I would assume that I had a much easier time finding speakers willing to talk about digital forensics in 2024 than was the case for DPC colleagues in 2011!

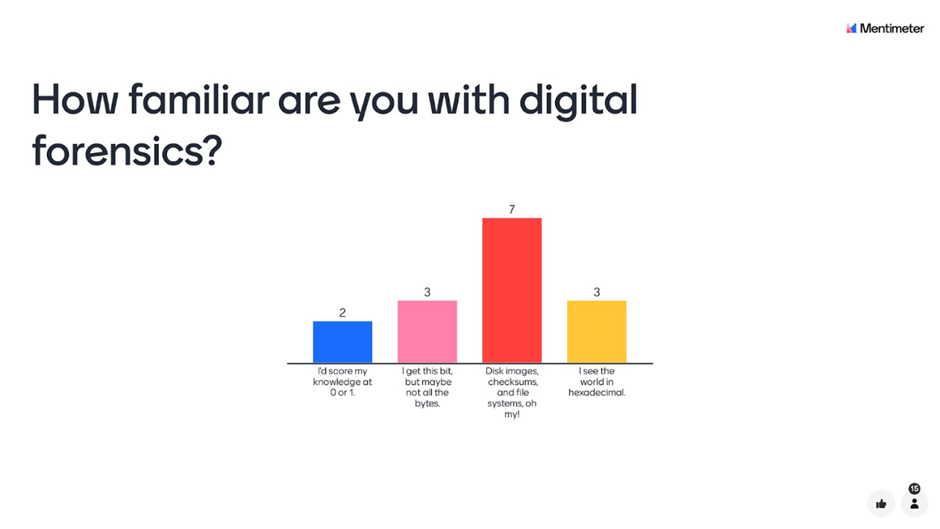

Above: A question Martin Gengenbach from the National Library of New Zealand put to attendees at our ‘Watch Party’ event on this topic suggests that most attendees had at least a basic understanding of digital forensics.

It was helpful to hear many of the speakers describing what they understand by the term digital forensics. They defined this in a number of ways, some focusing on the definition provided by Jeremy Leighton John in the DPC Technology Watch Report, and others drawing on the DPC Handbook and other resources.

- Digital Forensics The application of scientific technical methods and tools toward the preservation, collection, validation, identification, analysis, interpretation, documentation and presentation of digital information derived after-the-fact from digital sources. Digital Preservation Handbook Glossary

- ‘forensics’ essentially refers to the process of in depth analysis of information that exists in the present, in order to reconstruct past events or objects, with the proffered interpretation being subject to scrutiny by others. Digital Forensics and Preservation

- Digital forensics is an applied field originating in law enforcement, computer security, and national defense. It is concerned with discovering, authenticating, and analyzing data in digital formats to the standard of admissibility in a legal setting. Digital Forensics and Born-Digital Content in Cultural Heritage Institutions

- Digital forensics is a branch of forensic science that focuses on identifying, acquiring, processing, analysing, and reporting on data stored electronically. The main goal of digital forensics is to extract data from the electronic evidence, process it into actionable intelligence and present the findings for prosecution. All processes utilize sound forensic techniques to ensure the findings are admissible in court. Interpol

Speakers were also asked to consider and describe what good practice actually looks like for digital forensics in our field of work, and I’ve summarised the answers to that question below.

-

For Callum McKean from the British Library good practice in digital forensics is all about enabling the widest array of options for our future curatorial colleagues. We can’t read every file type right now and we don’t have the resource to do all the necessary work. A capture and ingest workflow based around digital forensics means you have the most authentic and complete copy of the digital content, and you can access this again in the future as our practices and tools evolve. We don’t know what that future might look like in terms of the technical landscape or archival practice, but we should take steps to ensure that we don’t inadvertently damage or destroy potential evidence in our workflows.

-

Leo Konstantelos from the University of Glasgow considered good practice to be engaging with the community. He stressed the importance of learning what others are doing and picking up recommendations on practices. Given the complexity of the content we are working with, this collaboration can be really beneficial. He was keen for us to find ways to create a community knowledge base of resources so we can more easily share relevant information. A useful resource that Leo shared in his presentation was a digital forensics workflow which has been published on COPTR.

-

Leontien Talboom from Cambridge University Library also highlighted collaboration as a key element of good practice and shared Leo’s wish for a resource hub that brings together relevant material relating to digital forensics. Her presentation had focused quite heavily on the documentation work she had been doing, both on information around the carriers, their type, brand and condition, and on documentation of processes, which can be used to help ensure other staff members can understand and work with this material. For example, she shared the guidance they have created on recognising different carrier types. She also highlighted the maintenance of equipment as being a key element of good practice in this field.

-

We were joined by members of the Digital Archival traNsfer, iNgest, and packagiNg Group (DANNNG). One of their key messages in relation to this question was that it is more important to think about individual aims and goals when using forensics techniques rather than setting hard and fast rules around good practice that everyone should follow. Dianne Dietrich gave an example around whether we should or shouldn’t create disk images - there is no single answer to this question as it depends on a variety of different factors. This is reflected in a resource this group has created. Disk Imaging Decision Factors is designed to guide someone through the different aspects that might go into this decision making process. Farrell described the importance of the community to create documentation and guidance collaboratively and Lara Friedman-Shedlov described good practice as making a faithful and authentic copy of the digital content when necessary. She stressed the importance of documenting your actions and communicating with users about what it all means (for example flagging up uncertainties and challenges around file modification dates).

-

The documentation good practice theme was expanded on by Thorsten Ries from the University of Texas at Austin. He pointed out that the tools used in digital forensics all have an impact on the record that is ultimately created. Even a different version of the same tool might create a very different record. Good practice therefore involves carefully documenting tools and processes and ensuring this information is available to our users so they can better understand how the record has been created. Documenting hardware and context is also important and will aid future understanding of what a record is, where it comes from and why it looks the way it does.

-

In our follow-on ‘watch party’ event, Martin Gengenbach from the National Library of New Zealand focused his presentation on maintaining good practice through policy. Good practice for him focused on the alignment of digital forensics techniques and decision making with policy statements, ensuring tools and processes worked together with policy to meet organizational needs. He shared some great examples of how this might look in practice from a variety of organizations.

-

In the discussion section at the end of the event, Lara Friedman-Shedlov turned the question around and suggested that as we are always going to be limited by the resources we have available to us, worrying about a one-size-fits-all ‘good practice’ is perhaps not helpful. She suggested that instead we should consider what is the best we can do in the circumstances that meets our current needs. William Kilbride added to the discussion to suggest that the area where we can best focus our discussions on good practice might be around reaching a robust understanding around the ethics of the work we are carrying out around digital forensics.

I made some observations at the start of this blog post about how this recent event differed to the DPC’s 2011 Briefing Day on this topic, but I’ll end with one common theme that brings these two events together. Jeremy Leighton John noted in his talk in 2011 that we should be cautious about using the term ‘forensics’ with our donors and depositors. This point was echoed by several of the speakers last week.

Brian Dietz, representing DANNNG, touched on the use of digital forensics for law enforcement and differences in trust around that process in diferent parts of the world. He asked whether we want to use the word ‘forensics’ to describe our digital preservation workflows when that term may not be seen in a positive light by some. Cal Lee suggested the term "bitstream-aware digital curation" was a more accurate representation of what digital forensics actually is in the context of our work. He made some interesting points around the evolution of the term ‘digital forensics’ and its changing emphasis over the last twenty years. There was some insight shared by both Cal and the DANNNG speakers around how practices that we have called ‘forensics’ in the past are becoming more and more a part our standard ways of working in digital preservation.

There was a lot of information shared throughout the event and a lovely collaborative feel in the virtual room, with so many good ideas flowing and generous sharing of links to resources and advice in the chat box. I’ve only captured a very small part of that in this blog post but do follow up on the resources that are available if this has sparked an interest.

Copies of the presentation slides are linked from the programme on our event page and DPC Members and Supporters can also see recordings of all the presentations and discussions by logging into the DPC website.

Thanks again to all of our speakers and attendees for making this such an interesting community discussion.

Read more...