![]() This year, DPC's Research and Practice team has been working on two studies commissioned by the UK Data Service as part of their Big Data Network Support. Both Preserving Social Media and Preserving Transactional Data will address the issues facing long-term access to this big, fast-moving data and will be published as Technology Watch reports. As part of Preserving Social Media, this series of posts examines some of the points of tension in the efforts of research and collecting institutions to preserve this valuable record of life in the 21st century.

This year, DPC's Research and Practice team has been working on two studies commissioned by the UK Data Service as part of their Big Data Network Support. Both Preserving Social Media and Preserving Transactional Data will address the issues facing long-term access to this big, fast-moving data and will be published as Technology Watch reports. As part of Preserving Social Media, this series of posts examines some of the points of tension in the efforts of research and collecting institutions to preserve this valuable record of life in the 21st century.

I'm Sara Day Thomson, Project Officer for the DPC, specialising in the pursuit of new ideas in digital preservation.

If you want to get involved, follow me on Twitter @sdaythomson and the DPC account @DPC_chatter to get the scoop on upcoming DPC events and activities!

Platform Restrictions: Why is it so difficult to use social media data for research and almost impossible to preserve this user-generated content in heritage collections?

Social media has spread across the UK at an increasing rate as communities embrace networked platforms in their everyday lives. It has grown through a rise in dynamic programming and the rise of 'open' platforms that allow users to create and share information with other connected users. The most prevalent forms of social media in the past five years—Facebook, Qzone in China, Google+, Instagram, Twitter, and Tumblr—contain a powerful record of life in the 21st century [1]. By spring of 2014, Facebook was ingesting approximately 6000 terabytes of data every day [2]. Twitter users generate over 500 million tweets a day equalling more than 2.2 terabytes, not including storage overhead and indexing [3]. Facebook alone has over 30 million users in the UK, potentially connecting them to nearly 1.5 billion users worldwide—that equals nearly 20% of the world's population as of 2015 [4]. Twitter reached 15 million users in the UK in 2013, and exceeded 315 million worldwide in 2015. As Internet reaches more and more developing countries across the globe with the help of mobile technologies, it is predicted that by mid-2016 over half of the world's population will be online and nearly 80% of them will engage with social media [5].

While the world continues to communicate, exchange information, and live their lives on social media, unprecedented amounts of data are being generated that could lead to significant discoveries about human behaviour and the spread of information and ideas. It could teach us about the flow of hateful speech and trends in charitable campaigns and lead to better governance of whole cities, nations, and continents. It could tell us what people are most afraid of and where they turn for guidance. It could teach us how communities react to violence and how they react to innovation and acts of heroism. It could empower scientists, researchers, governments, and citizens with the capacity to predict the outcome of disease outbreaks, natural disasters, economic crises, and political elections. It could help social scientists to understand subsets of the population previously hidden or silenced.

But mostly, it's used to help large corporations sell us stuff.

While the exploitation of user data has become a lucrative trade in the corporate sector, the development of social media research and of social media heritage collections have faced significant setbacks. For one, it's expensive. The cost of accessing social media data is often prohibitive for public and non-commercial organisations, such as universities, libraries, and archives. However, in my opinion, the greatest obstacle to research and non-commercial institution access to social media data are the legal restrictions imposed by platforms and their third party resellers.

Twitter, for instance, provides access to its data through APIs, but severely limits how that data can be used and shared through their Developer Policy and Agreement. Gnip, the official Twitter reseller (owned by Twitter), also restrict how data obtained through their services can be used and shared. Facebook provides VERY limited open access through APIs and only Datasift sell Facebook Topic data, highly-coveted user content for conducting social science research and developing cultural collections. The long and the short of it is that trying to obtain social media data for research or non-profit heritage collections is much like trying to eat soup with a fork. It's possible but it requires a lot of effort for very little return.

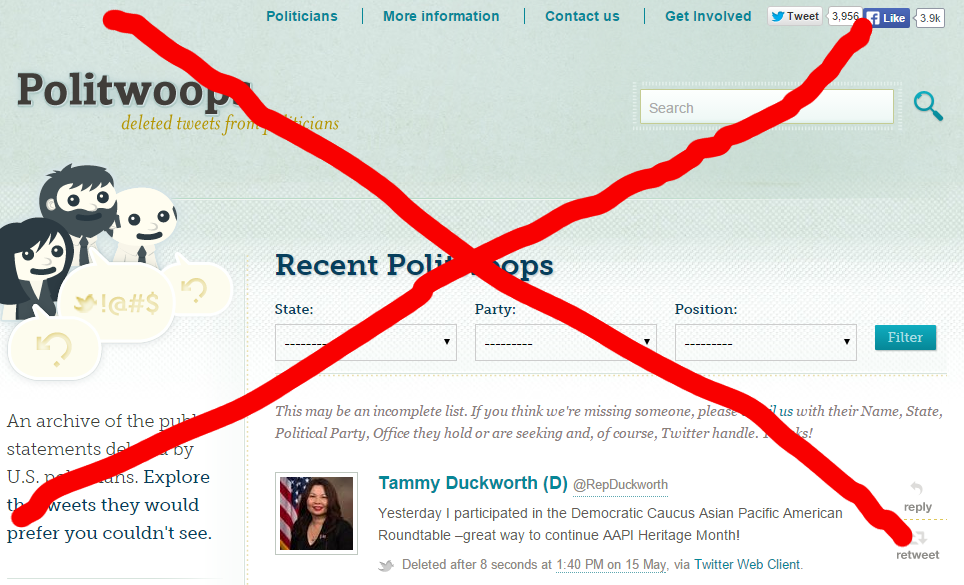

And the situation does not look promising in the years ahead. Though Twitter continues to promote the use of Twitter data for social good, it also continues to shut down non-profit initiatives who step outside the letter of Twitter Law. In June of this year, for example, Twitter rescinded API access from Politwoops in the US, a non-commercial website that captures and publishes the tweets deleted by US government officials and campaign accounts. Twitter cited a violation of their user agreement, which forbids the re-publication of deleted content. Despite a 2012 agreement with the site, Twitter shut down Politwoops, who openly undermined the platform's exclusive data ownership, ownership partially established through that same user agreement they claimed Politwoops was violating. Throughout August, Twitter proceeded to rescind API access from Politwoops sites in more than 30 countries who have been collecting deleted tweets since Open State launched the site in 2010. To prevent the loss of valuable public records, Open State uploaded over a million deleted tweets from across 35 countries to the Internet Archive for preservation, but Politwoops will no longer be collecting newly deleted tweets by our politicians and state officials.

This episode with Politwoops reflects the bigger picture of social media data ownership. In 'The Politics of Twitter Data', Puschmann and Burgess articulate:

'It follows that only corporate and government actors—who possess both the intellectual and financial resources to succeed in this race—can afford to participate, and that the emerging data market will be shaped to their interests. End users (both private individuals and non-profit institutions) are without a place in it, except in the role of passive producers of data' (p. 52).

It should be emphasized here, again, that platform ownership of user data is largely established through Terms and Conditions where most platforms (not just Twitter) have decided they own user data, because the data is created using their service and held on their servers. Whether or not these types of user agreements constitute 'consent' for all types of re-use of that data is currently under debate (see for instance the report by Fred H. Cate). In the meantime, making progress in research and non-commercial heritage collections will face continued opposition from the platforms and resellers who profit from exclusive rights to the content generated by its users. In other words, making progress in using social data to HELP the users who create that data and in preserving that data for future generations face a long, hard road ahead.

CEO of Gnip says it himself: 'Data is not free, and there's always someone out there that wants to buy it. As an end-user, educate yourself with how the content you create using someone else's service could ultimately be used by the service-provider' (Jud Valeski, CEO of Gnip, qtd. in Puschmann and Burgess). Though I admit I read those words with a hint of derision, coming as they do from a company instructing us to educate ourselves about how they plan to take advantage of us or else we have no place to complain when they do. To be clear, I am happy social media platforms have found a means of financially supporting their infrastructures and even making a profit—they provide an essential public good. However, the restrictions that prevent user data from helping the individuals who have created it should greatly concern both users, platforms, and policy-makers.

CEO of Gnip says it himself: 'Data is not free, and there's always someone out there that wants to buy it. As an end-user, educate yourself with how the content you create using someone else's service could ultimately be used by the service-provider' (Jud Valeski, CEO of Gnip, qtd. in Puschmann and Burgess). Though I admit I read those words with a hint of derision, coming as they do from a company instructing us to educate ourselves about how they plan to take advantage of us or else we have no place to complain when they do. To be clear, I am happy social media platforms have found a means of financially supporting their infrastructures and even making a profit—they provide an essential public good. However, the restrictions that prevent user data from helping the individuals who have created it should greatly concern both users, platforms, and policy-makers.

Before I leave, I just want to direct readers to a couple of resources for social media users. Though many of the readers of this post may be conscientious when it comes to privacy settings, there are a number of services to help users 'unveil' how social media platforms use their data. Digital Shadow shows where your Facebook data has been used and AVG PrivacyFix will perform a privacy audit of your Facebook and Google Accounts.

For a more positive spin on the non-commercial use of social media, watch this space. Regardless of all the paranoid anti-corporate ranting above, there are social media researchers and heritage institutions doing (very carefully) really cool stuff with social media.

Notes

[1] http://was-sg.wascdn.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Slide028.png

[2] https://code.facebook.com/posts/229861827208629/scaling-the-facebook-data-warehouse-to-300-pb

[3] https://about.twitter.com/company

[4] http://www.slideshare.net/wearesocialsg

[5] http://wearesocial.net/tag/statistics

Citations

Puschmann, C and Burgess, J (2014), 'The Politics of Twitter Data', In K Weller et. al. (Eds) Twitter and Society, New York: Peter Lang Publishing.