Mashal Ahmad is a Software Developer and Kathryn Cassidy is a Software Engineer, both working for the Digital Repository of Ireland.

During the current pandemic, we have seen some wonderful examples of how communities can come together in the face of adversity. We’ve seen everything from viral videos of Italians in lockdown singing from their balconies, images of teddy bears in windows, and a huge range of community efforts to help vulnerable people in their areas. One great initiative that emerged among maker and tech groups was the 3D printing of face shields, at a time when personal protective equipment for health professionals was in short supply world-wide.

View of the Face Shield 3D Model as it appears in the DRI Repository 3D viewer (CC-BY 4.0)

The emergence of affordable consumer 3D printers enabled this amazing response from maker and tech groups. The fact that these groups and individuals were able to meet the demand for PPE, bridging the gap while commercial producers ramped up their production capacity, shows us that 3D printing is becoming a ubiquitous technology. Indeed 3D technologies and 3D data, in the past associated with certain specific industries, are now becoming standard tools across all kinds of unexpected fields.

With almost everybody now owning powerful smartphones and tablets, it is increasingly easy and cheap to capture 3D models of real-world objects. At the same time, support for displaying 3D content is becoming more widespread, with many user apps available, and social media platforms such as Facebook and Google adding 3D support r to enhance their user experience.

3D content comes, however, with a whole host of problems from a preservation perspective. There are a huge number of different hardware and software platforms as well as data formats and standards, many of which are proprietary. There is a very real concern over how we can ensure that the wealth of 3D data currently being produced will continue to be accessible and available for viewing and interacting with in the future.

The Digital Repository of Ireland has recently started working on collecting and preserving 3D cultural heritage data with the potential for reuse in various domains such as open science, education, research and tourism. As a Trustworthy Digital Repository for the Humanities, Social Sciences and Cultural Heritage communities we are beginning to encounter collections of 3D models of museum artefacts, archaeological digs and historical buildings. Even with a defined remit, we are finding a large variation in file formats, ranging from large LiDAR point clouds and photogrammetry data to models created specifically for 3D printing.

A single 3D digital object often consists of several source files including point clouds, models and associated 2D image files for rendering and texturing. The workflow for preserving 3D data is further complicated by the fact that in order to replicate the exact scene or model we often need to preserve a lot of additional metadata related to devices, scanners, tools and equipment used to capture the data.

Our initial test dataset was provided by Transport Infrastructure Ireland (TII). They gave us a number of terrestrial scans of various archaeological monuments, bridges and famous statues. The scans of these artefacts were in raw forms such as point clouds. Often these consist of ASCII-based files with point coordinates, which are good for preservation in that they can at a minimum be opened in a text editor in future, which would allow feature extraction. They tend to be very large, however (each file being between 6-8GB), and it’s not always easy to display them or allow users to interact with them.

We thus reconstructed 3D replicas of the scenes using technologies like open3D and Cloud Compare and then we removed unnecessary noise with Bender and Meshlab etc. These lightweight 3D reconstructed meshes or replicas may not maintain scientific integrity and they lose a considerable amount of detail compared to the source files. For this reason we are storing and preserving the original files alongside these surrogate versions. The lightweight surrogates will typically form the Dissemination Information Package (DIP) for most regular uses, but it will also be possible to access the original files and the metadata that identifies the software and platforms that would be needed to use these. We are also exploring a variety of open formats and standards such as IFC, Collada and glTF that are helping to make 3D content more interoperable. It may be possible to migrate some of the source files to these more interoperable standards and again, preserve these alongside the source files.

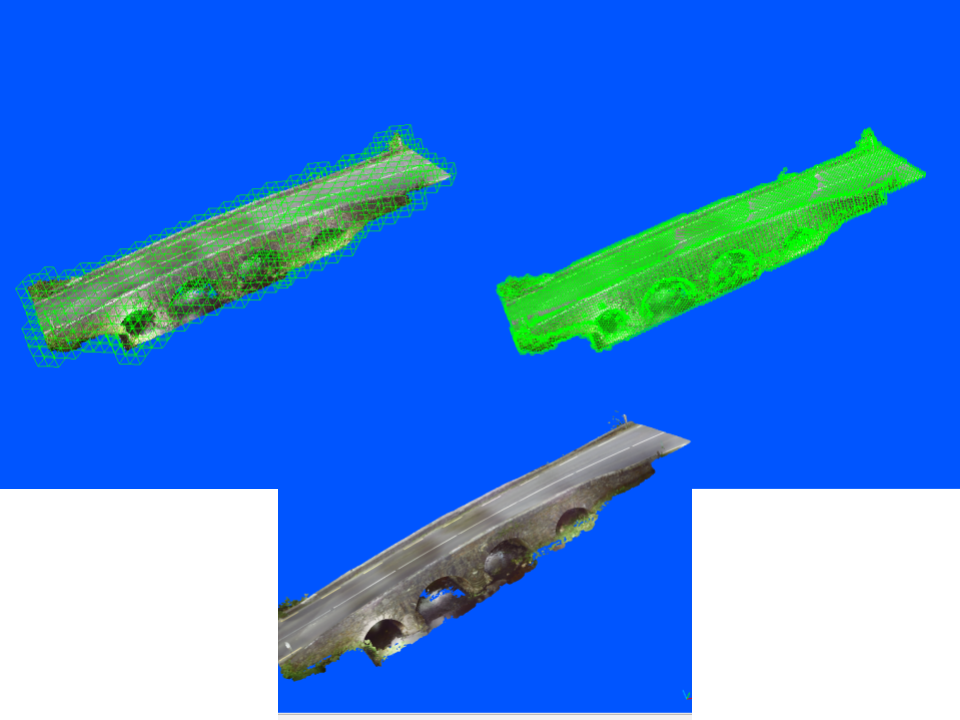

3D Surface reconstructed of Beheenagh Bridge , Co. Kerry from the TII collection with octree depth 5,7 and 10 (CC BY 4.0)

Another possible preservation approach, but one that we haven’t yet explored, is an emulation strategy. In this approach, we would create an emulated environment using the software that is needed to open and visualise the original source files. As with other software preservation efforts, this approach is complicated by issues such as software licencing. It’s a more difficult task, but one we are keeping an eye on as a possible future solution.

At the moment, DRI is working on aggregating some of this 3D content to the Europeana platform (http://europeana.eu/) as part of the Common Culture project (https://pro.europeana.eu/project/europeana-common-culture). Europeana has its own Europeana Data Model to make the metadata interoperable and Europeana Publishing Framework for improving the quality of metadata and allowing for better showcasing of content. Europeana strongly encourages complex digital objects, such as 3D, to be made available in the form of a web-embeddable viewer. For aggregation to Europeana the 3D viewer should use the oEmbed protocol and we are working on it currently.

To add support for an embeddable 3D viewer we had several options. We looked at some of the most popular online viewers in use by other Europeana content providers. These include commercial hosting platforms such as Sketchfab, as well as self-hosted solutions such as 3DHOP or Smithsonian voyager. Although Sketchfab has an advantage of no overheads in terms of storage capacity for the content providers and aggregators, it does impose limitations in terms of cost, size of models, number of models, formats etc. The self-hosted options also tended to be limited in the range of formats that they could support. Therefore, we decided to build our own 3D viewing tool using the JavaScript Three library. We have successfully integrated the 3D viewer into our Ruby-on-Rails-based repository platform, giving us support for more than 40 formats and no limitation on the size or the number of models, beyond our own storage capacity. We are hoping to open source this viewer soon and we are looking forward to working on more fun features including VR and virtual tours.

This work was well underway before COVID-19 hit, but the pandemic, and the many wonderful community responses, made us also think about what small ways we as an organisation might be able to help. You can read more about the areas of support identified by the Digital Repository of Ireland in our ‘COVID-19: Playing our Part’ statement (https://www.dri.ie/covid-19-playing-our-part). As part of this support, we decided to use our preservation infrastructure to capture and preserve some of the 3D printing models that maker groups have been using to create face shields for healthcare workers. In fact, our software engineer Mashal went one step further and designed our own 3D face shield. The face shield model is open source and can be viewed and downloaded from the Repository at https://doi.org/10.7486/DRI.g732sz11t.