Amsterdam Museum and Project Partners: The Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision, University of Amsterdam, Waag Society, National Coalition on Digital Preservation and old inhabitants, (ex) DDS employees and DDS affiliated web archaeologists

On 15 January 1994 De Digitale Stad (DDS; The Digital City) opened its virtual gates. In 2001 DDS, the website, was taken offline. In this case study of web archaeology we will answer the questions: how to excavate, reconstruct, preserve and sustainably store born-digital heritage and make it accessible to future generations?

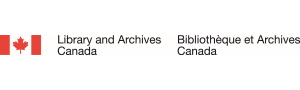

The different interfaces (cityscapes) of The Digital City

DDS is the oldest Dutch virtual community and played an important role in the internet history of Amsterdam and the Netherlands. DDS is an important historical source for the early years of the internet culture in the Netherlands. The first virtual city in the world and its inhabitants (‘users’) produced objects, ideas and traditions in new digital forms such as web pages, newsgroups, chat, audio and video. DDS made the internet (free) accessible for the first time to the general public in the Netherlands, was a testing ground and operated at the cutting edge of creativity, information and communication technology and science.

Help! Our digital heritage is getting lost!

“The world’s digital heritage is at risk of being lost”, the UNESCO wrote more than a decade ago in 2003, and “its preservation is an urgent issue of worldwide concern”. The UNESCO acknowledged the historic value of our 'born digital' past and described it as “unique resources of human knowledge and expression”. Only one year ago in 2015, Google's Vint Cerf warned, again, for a 'digital Dark Age': “Humanity’s first steps into the digital world could be lost to future historians. We face a forgotten generation, or even a forgotten century”.

Out of the box

The acquiring and preservation of digitally created expressions of culture have different demands than the acquiring and preservation of physical objects. This is a new area for the heritage field in general and the Amsterdam Museum in particular. The museum has to cross boundaries, and get out of its comfort-zone to break new ground in dealing with digital heritage. To seek out new technologies, and new disciplines. To boldly dig what the museum has not dug before. How to dig up the lost hardware, software and data? And how to reconstruct a virtual city and create a representative version in which people can 'wander' through the different periods of DDS and experience the evolution of this unique city? The challenge is: can we –and how?- excavate and reconstruct The Digital City, from a virtual Atlantis to a virtual Pompeii? Given the bias in our knowledge and the complexity, nature and scope of the matter, we needed the expertise of specialist institutions. So we teamed up with the University of Amsterdam, Dutch Institute for Sound and Vision, Waag Society and started the project "The Digital City revives".

The goals of "The Digital City revives"

- Reconstruct and preserve DDS.

- Provide insight into the (existing and new) processes, techniques and methods for born-digital material and the context in which they are found, to excavate and reconstruct.

- Ask attention to the danger of ‘digital amnesia’, especially in the domain of the museums.

- To provide museums and organizations with specialized knowledge about the reconstruction of born-digital heritage and lower the threshold for future web archaeological projects. Disseminating knowledge about new standards for archives on the storage of digital-born heritage in ‘The 23 Things of Web Archaeology’ and a ‘DIY Handbook of Web Archaeology’.

- Make DDS data ‘future-proof’ in making the digital cultural heritage:

- Visible (content): promoting (re)use of DDS.

- Usable (connection): improving (re)use of DDS collection by making it available by linking and enriching data.

- Preservable (services): maintain DDS sustainable and keep it accessible.

Main achievements: bringing DDS back alive!

A. Crowdsourcing

The first step was to find the data! There was no DDS archive, so the only chance of finding ánd piecing the DDS data together lay with people: old inhabitants, former DDS employees and volunteers. Web archaeologist Tjarda de Haan had worked for DDS and had connections with former residents and DDS employees. As well calls were sent out through mailing lists, blogs and social media. Especially Twitter and Facebook proved to be indispensable tools. The Amsterdam Museum organized the ‘Grave Diggers Party’ with the Waag Society. A party with a cause. A party to re-unite people and collect lost memories, both personal and digital. We excavated great artefacts. We collected old servers, raw data, including backups of the city squares, houses, projects, a 'freeze' of DDS of 1996, a radio play for DDS and a lot of physical objects, like manuals, magazines, photographs, videotapes and an original DDS mouse pad.

B. Tools and methods

To start with the reconstruction of the lost and found DDS data, bit by bit, byte for byte, we used several tools and methods. We used old systems to extract the raw data from the different storage systems that we recovered. We used eForensics, DeNISTing, Virtual Machines and emulation technologies. In the end the students and web archaeologists were able A. to reconstruct DDS3.0, the third and most known DDS interface, and B. to build a replica using emulation, DDS4.0. An enormous achievement, and a huge step into the new (scientific) discipline web archaeology!

Now DDS has been included in the permanent collection of the museum. The audience can see our first web archaeological excavations, the DDS ‘avatars’, and ‘experience’ DDS by taking place behind an original DDS public terminal, another excavation, and watch television clips about DDS. In the nearby future we aim to enable people to interact with the replica DDS, and take a walk through the historical digital city.

Next level

With the joint forces of our partners, including museums, innovators, creative industries, archives and scientists, we will face our last major challenges: how to open up and sustainable store the DDS data into e-depots, how to present the DDS born-digital heritage in a museum context for future generations, how to share our knowledge and lower the threshold for future web archaeological projects and how to contribute to a hands-on jurisprudence of privacy and copyright for future web archaeological projects?

DDS has been included in the permanent collection. The audience can see our first web archaeological excavations (the DDS ‘avatars’) and ‘experience’ DDS in the Amsterdam Museum by taking place behind an original DDS public terminal and watch television clips from 1994 about DDS. In the nearby future we aim that, people can interact with our lost and found born-digital heritage, the replica of DDS, and take a walk through the historical digital city.

DDS has been included in the permanent collection.

- Find out more: http://hart.amsterdammuseum.nl/re-dds