At first glance, the terms ‘social media’ and ‘long-term preservation’ do not seem to belong in the same sentence. The two terms are perhaps even incompatible, mutually exclusive, and contradictory.

In some senses, that’s true. As far as using social media goes, it is designed for Right Now. Social media users tweet, post, share, like, and blog to communicate and publicise information about what’s going on in the present and immediate future.

But I think you could say that’s also true (in principle) of most ‘traditional’ news outlets: broadcast news and even those old ink and paper contraptions. But that hasn’t stopped the British Library from collecting every circulated newspaper in the UK and Ireland since 1840 in a state-of-the-art warehouse facility. And (as far as I’m aware) there isn’t a major public debate about the value of preserving newspapers and news broadcasts. The consensus is that, yes, keeping a record of current events is important for researchers, decision-makers, and every other responsible citizen of the future.

But I think you could say that’s also true (in principle) of most ‘traditional’ news outlets: broadcast news and even those old ink and paper contraptions. But that hasn’t stopped the British Library from collecting every circulated newspaper in the UK and Ireland since 1840 in a state-of-the-art warehouse facility. And (as far as I’m aware) there isn’t a major public debate about the value of preserving newspapers and news broadcasts. The consensus is that, yes, keeping a record of current events is important for researchers, decision-makers, and every other responsible citizen of the future.

Of course it’s not a one-to-one comparison – the dynamics and conditions of social media differ from ‘traditional’ news. The News (capital N) is delivered by trained professionals within the context of regulated institutions (when it’s at its best…). Social media comes from literally anyone with access to the internet and a device with internet capability and a keypad. From the President of the United States to every great aunt Mildred who has mastered Facebook, social media users are everyday people who hold a newfound power to report information directly to a public (global) audience. This power leads to the general availability of informal statements and opinions which are very difficult to get back once they have been committed to internet memory. Just ask Justine Sacco or Paul Chambers.

While a sudden compunction or change of heart may induce someone to delete content, deletion does not necessarily eradicate all trace. Once a (perhaps injudicious) post makes it to the scandal-mongering public arena, it will get copied, screengrabbed, re-posted, and circulated out of anyone’s control to stop it. Even a seemingly harmless post could later, under new circumstances, make someone vulnerable or at risk. While platforms usually enforce policies to prevent access to users’ deleted content, even they do not have the power to overcome an internet frenzy. And despite these policies to prevent access to deleted content, many platforms still retain copies of deleted content on their servers.

So, yes, social media and long-term preservation are awkward bedfellows. On one hand, we’re worried about this trace of social media activity. The arguments on both sides of the Right to Be Forgotten fence acknowledge the risks arising from the capture of and accessibility to potentially personal information on the internet. On the other hand, we are eager to exploit the opportunities provided by the traces left by users on social media. Social media data analytics provides researchers the opportunity to learn about previously invisible demographic groups and to discern patterns far too complex to identify in conventional research data sets.

The preponderance of public shaming and corporate manipulation surrounding the use of social media data gives a pretty bleak picture. The dangers imposed by misuse of these data, however, should not overshadow the potential of using this data to bring about positive change. However, researchers motivated to use social media data for the public good face more restrictions to social media data than Fortune 500 companies interested in using it to line their pockets.

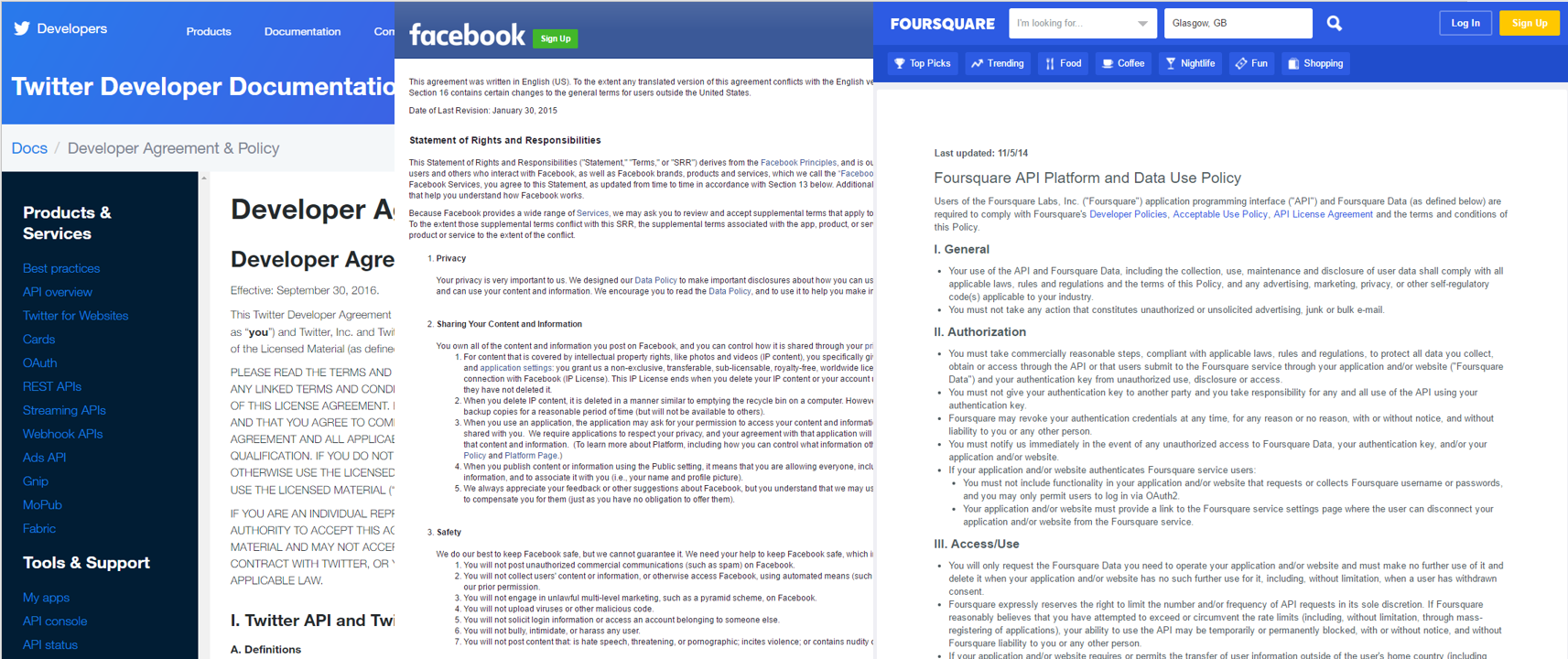

I don’t begrudge social media platforms a means of turning a profit. They provide an important service and continue to enable the creation of communities previously unable to discover each other or to organise. However, the cost of purchasing social media data from platforms prevents non-commercial researchers from using this data for the good of society. Furthermore, to protect the profits made by selling consumer data, platforms have enacted policies that inhibit the growth and impact of research. Namely, they enforce Terms of Use that prohibit the sharing of these data, including the deposit of data into research repositories or archives. Without the ability to preserve social media data sets and make them accessible to other researchers, social media research cannot fully realise its potential. Social media platforms have no contractual or legal requirement to preserve individual users’ data, which makes any research based on this data vulnerable. When researchers cannot access the data underlying other researchers’ analysis, the research cannot be validated and therefore cannot be built on.

I don’t begrudge social media platforms a means of turning a profit. They provide an important service and continue to enable the creation of communities previously unable to discover each other or to organise. However, the cost of purchasing social media data from platforms prevents non-commercial researchers from using this data for the good of society. Furthermore, to protect the profits made by selling consumer data, platforms have enacted policies that inhibit the growth and impact of research. Namely, they enforce Terms of Use that prohibit the sharing of these data, including the deposit of data into research repositories or archives. Without the ability to preserve social media data sets and make them accessible to other researchers, social media research cannot fully realise its potential. Social media platforms have no contractual or legal requirement to preserve individual users’ data, which makes any research based on this data vulnerable. When researchers cannot access the data underlying other researchers’ analysis, the research cannot be validated and therefore cannot be built on.

To summarise, the fundamental issues at the heart of the conversation about preserving social media are – in keeping with the trends of this blog post – at odds. On the one hand, keeping it all could put social media users like me, and probably you, too, at risk. On the other hand, it might save the planet.

We need a solution that resolves these seemingly contradictory concerns. We need a solution that acknowledges and actively manages the risks associated with the sharing of personal information. We also need a solution that makes access to social media data easier and more affordable for non-commercial researchers. We need a solution that preserves social media data sets to a professional standard in order to improve reproducibility for research. We need to preserve these data so that decision-makers can use new research confidently to inform policy and public programmes.

In my humble information professional opinion, that solution starts with public awareness and effective communication on the part of specialists who can help clarify the risks and opportunities of social media. This communication also requires the backing of the institutions and governments with the power to support these specialists through policies and funding. This solution starts with targeted and significant collaboration between researchers and information professionals.

I look forward to further exploring the formulation of this solution this summer at Web Archiving Week hosted by the School of Advanced Study at the University of London and the British Library. I hope to see you there and hear what you have to say about the way forward with the long-term preservation of social media.

For more information and to register: http://www.sas.ac.uk/events/event/7186

Comments

It frustrates me that memory institutions haven't rallied to addressed this. The TOCs are demonstrably unconscionable. we are unable to deliver our social, moral and legal obligations to archive humanity, without breaching the TOCs, but there is no avenue for negotiating the TOCs against our collecting remits.

RSS feed for comments to this post