Over the last 18 months I have been fortunate to have the opportunity to reflect, research, and synthesise with colleagues, what we have learnt about costs and benefits from digital curation and preservation. The results are now published in a cost-benefit advocacy toolkit released by the Consortium of European Social Science Data Archives (CESSDA).

It was a small project focussed on the needs of social science data archives but much of what it has done will be of interest to anyone involved in digital preservation and repositories.

So what have we learnt over recent years, and to borrow from the title of this blog, are we there yet?

The answer to that question is going to have to be a personal viewpoint, and largely from a UK and European perspective, but I hope it is largely applicable to most practitioners and countries.

My benchmark starts a decade ago with the UK e-Infrastructure Strategy for Research Preservation and Curation Working Group. This working group drawn from libraries, research data services, and related bodies such as the DPC was charged with addressing the need for curation and preservation as part of the e-infrastructure for research and helping to define the development of this infrastructure. Its report was published in January 2007.

One of our tasks was to pull together evidence for the funding case to Government particularly to cope with the growing role of data in research.

All my colleagues in data archives were able to provide the annual budgets for running their services. Numbers varied greatly from service to service. Was digital curation and preservation expensive? How did the different disciplines compare? To get a rough comparison, the cost of each service was divided by the overall research budget of the research council which funded them. The results proved remarkably consistent, with the costs of all the existing data archives representing between 1.4 -1.5% of their respective research council budgets.

Even so, there were still big gaps in our knowledge of costs. Costs within institutions and institutional repositories (where significant volumes of research data reside that are not in national/international archives) were largely unknown or unknowable.

Asking colleagues about benefits and could we quantify them proved an even bigger challenge. We had a lot of generic statements about benefits but nothing that could be easily quantified.

The cost-benefit advocacy toolkit

Over the last decade, some of these gaps in our knowledge have begun to be filled. It has been a slow, painstaking development of methods and tools, and evidence gathering by projects such as Keeping Research Data Safe, the 4C project, and a series of economic impact studies for different data services.

The CESSDA SaW project funded by Horizon 2020, devoted part of one of its work packages to compiling a cost-benefit advocacy toolkit. This has aimed to draw together available evidence and tools for costs, benefits, and impact and to do so in a way to help even the smallest archives with advocacy, and understanding of key methods and evidence.

The toolkit is comprised of:

- A User Guide;

- Three Factsheets (Benefits, Costs, and Return on Investment);

- Four Case Studies from Social Science Data Archives (ADP in Slovenia, FSD in Finland, LiDA in Lithuania, and UKDS in the UK);

- Two Worksheets (the Archive Development Canvas, and the Benefits Summary for a Data Archive);

- A Deliverable Report describing how the toolkit was developed.

In addition, the Toolkit describes and links to a number of pre-existing external tools and relevant studies. You can access the Toolkit and download any components from here.

Key findings and evidence

I would like to present some of the key findings and evidence in the Benefits, Costs, and Return on Investment Factsheets that I think will be of widest relevance and interest for those working in digital preservation and repositories.

Repositories are appreciating assets

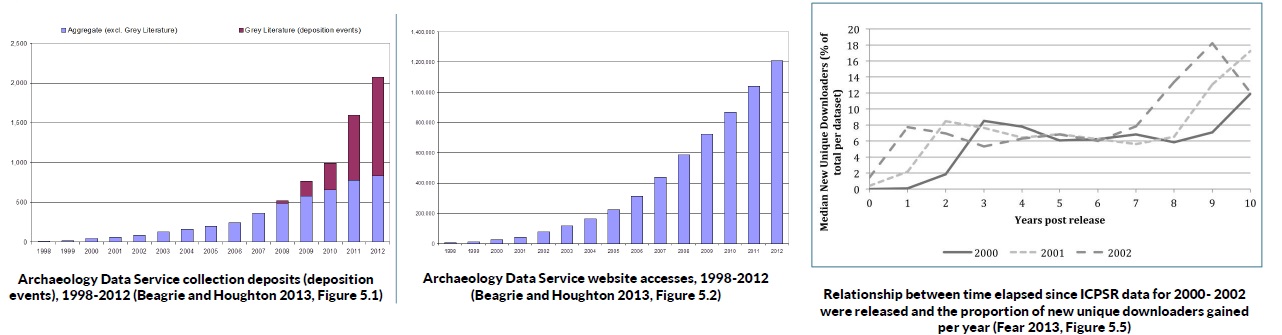

A repository tends to develop a critical mass of content, expertise and users over time. From the point they are established, repositories (or at least well-run repositories) grow the breadth and depth of their collections, their tools and infrastructure, training and support, professional networks, user base, and impact. They are appreciating assets that grow in value.

As such they are different to other tangible physical research infrastructure such as high-performance computers, research ships, or physical facilities. Typically, these are depreciating assets, with high initial use but declining value over time.

This has significant implications for how or when we measure impact of archives, and how we fund or advocate for them.

Archives are appreciating assets – extract from the CESSDA SaW Return on Investment Factsheet http://dx.doi.org/10.18448/16.0002 .

Data Archives provide high efficiency gains for research, teaching and learning

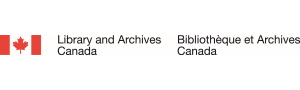

Over the last 5 years, a series of studies authored by John Houghton and myself have examined the value and impact of 4 very different research data archives: the Economic and Social Data Service (which became the UK Data Service); the Archaeology Data Service; the British Atmospheric Data

Centre; and the EMBL European Bioinformatics Institute. These archives vary substantially in scale, services, and disciplinary focus. Each of the studies examined efficiency gains (in terms of saving time) for a range of users. The funders, funder requirements and coverage differed from study to study but they all showed a consistent pattern and very high efficiency gains for their users.

Data archives have high efficiency gains for research, teaching and learning – extract from the CESSDA SaW Benefits Factsheet http://dx.doi.org/10.18448/16.0004

The Costs of Inaction

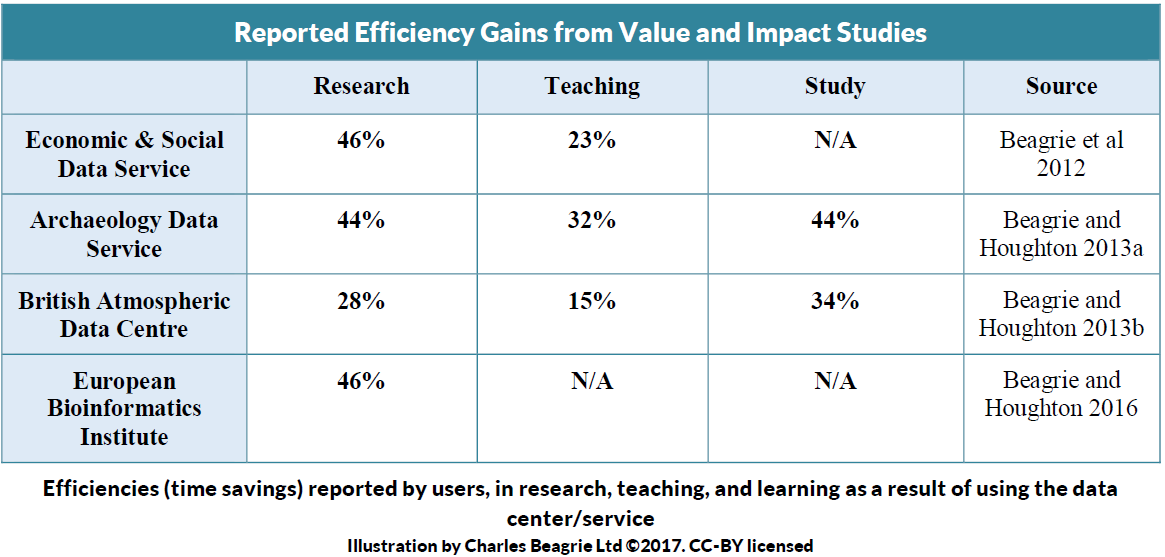

These efficiency gains are from mature established data archives. How can we evaluate immature archives or the case for creating new ones? Here the Toolkit emphasises the potential importance of thinking counter-factually. What would happen if there was no archive? Counter-factual evidence is difficult to gather and this remains an understudied approach. There are a few great examples for other preservation domains (I am a big fan of AVPreserve's Cost of Inaction Calculator for Audio visual archives and its promotional video).

The CESSDA SaW Return on Investment factsheet has pulled together what evidence we have for counter-factuals for data repositories. These are from studies in different disciplines, at different dates, and all are partial and narrowly focussed. However, they variously consider what happens when research data is archived by individual researchers.

I have ordered the reported findings in terms of total data loss, partial data loss, access (data requests fulfilled), and delay (the elapsed time until requests are fulfilled). The loss of data, loss of access, delays and inefficiencies are in many ways the flip-side of the high efficiencies seen for users of data archives. They contrast sharply with the excellent preservation record, very high fulfilment rates, and rapid online access rates of public data archives. As argued earlier, the public data archives also are appreciating as opposed to depreciating assets with improving rather than decreasing trends in value over time.

The Costs of Inaction: reported metrics for archiving via individual researchers – extract from the CESSDA SaW Return on Investment Factsheet http://dx.doi.org/10.18448/16.0002

Digital Preservation Costs

The costs of data curation and digital preservation have been the focus of a range of research projects in recent years and a selection of tools and a body of knowledge has emerged.

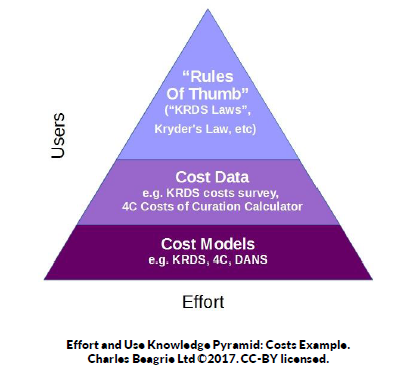

The toolkit uses a tripartite pyramid (Costs Models, Cost Data, “Rules of Thumb”) as a means of understanding existing work, each building on (and requiring the existence of) the others in terms of a knowledge-base, and each requiring different levels of effort.

A tripartite pyramid for understanding different digital preservation cost tools- extract from CESSDA SaW Costs Factsheet http://dx.doi.org/10.18448/16.0003

Cost “Rules of Thumb” or “Laws” are simple observations from existing cost data and projection of existing trends. These costs trends may hold for many years or even decades but eventually may alter: unlike laws of nature, which are fixed. They are very simple to apply and often very influential in business planning. “Moore's Law” and “Kryder's Law” have been critical in shaping development plans for industries in the IT sector.

In digital preservation costs research generally, the major focus has been on developing cost models, and then gathering and comparing of cost data. However, a general understanding of rules of thumb and trends within this work is likely to be useful to all, particularly those with fewer resources for gathering activity-based cost data or utilising cost models.

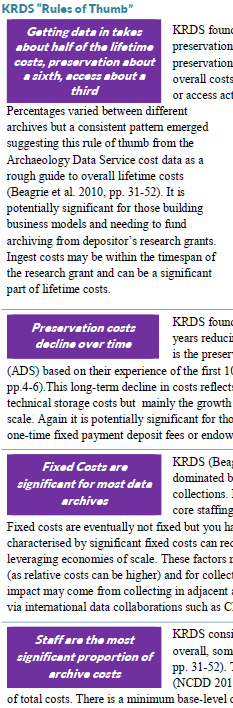

Some of the key findings from the Keeping Research Data Safe (KRDS) research projects on digital preservation costs were distilled in the CESSDA SaW Costs Factsheet. These rules of thumb for digital preservation costs will not be universally applicable but will probably be valid for most readers of this blog and their repositories (and for social science data archives, the “designated community” for CESSDA and the toolkit).

Digital Preservation Costs Rules of Thumb from the Keeping Research Data Safe (KRDS) projects – extract from the CESSDA SaW Costs Factsheet http://dx.doi.org/10.18448/16.0003

The value of Digital Preservation and Curation

So are we there yet?

Well we can now at least put a value on the impact of a range of mature data repositories and the curation and preservation they enable. Existing studies show a consistent and high return on investment of around 5-6 times the investment in the services.

Return on Investment for the Economic and Social Data Service – extract from the CESSDA SaW Return on Investment Factsheet http://dx.doi.org/10.18448/16.0002

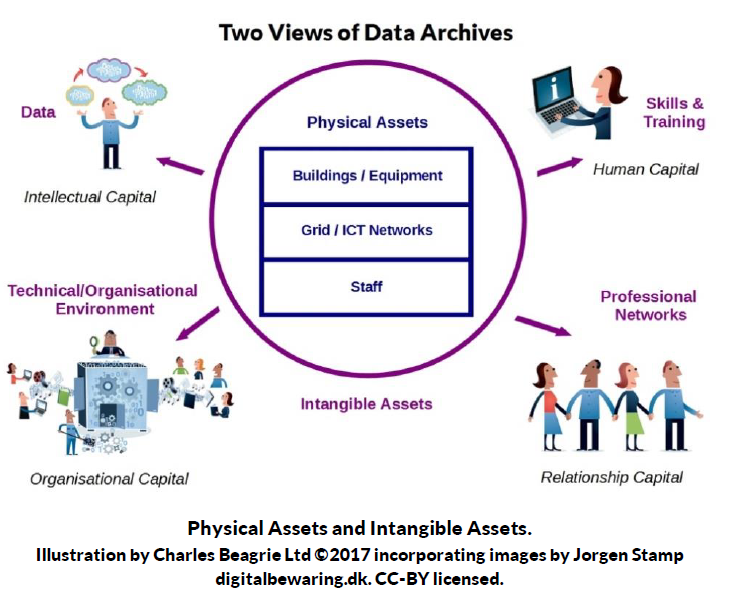

The value of repositories and the curation and preservation they undertake is a complex issue. A traditional view of research data infrastructure and assessing its impact has tended to focus on its physical assets: its buildings and equipment, IT networks, and staff.

In recent years, the importance of research data as an intangible asset has been increasingly recognised. However, arguably this still provides only a very partial view of the work and benefits of repositories. A data repository is not solely about data: there is a broad spectrum of value-added activities.

Another helpful way of thinking about and advocating for repositories focuses on all the intangible assets and value-added activities undertaken and the benefits these bring to stakeholders.

Arguably, the roles of repositories as “competency centres” in fostering skills and training; developing tools, standards and ontologies; and disseminating innovation in research data management practice, within their countries and disciplines, can be as important as the data they hold.

Physical Assets and Intangible Assets -extract from CESSDA SaW Benefits Factsheet http://dx.doi.org/10.18448/16.0004

So we have come a long way in evolving our knowledge and thinking about value, costs and benefits over the last decade. There is still more to do (for example extending our counter-factual evidence) but I hope the Toolkit will help institutions to continue to build on achievements to date.

The toolkit is openly licensed, Creative Commons By Attribution (CC-BY) or Share Alike when required (CC-BY-SA), and designed for ease of use for even the smallest repositories.

We hope it may also be helpful for teaching and learning the fundamentals of costs and benefits by students and in professional development by existing practitioners. Try it out!

Comments

RSS feed for comments to this post